With a plain white paper cup decorated by the wordplay “a wise man does not devote himself to love but the beautiful China belief”, a hutong cafe can harvest over ten thousand posts on Little Red Book, a social media and e-commerce platform. The innovative combination of traditional Chinese doughnuts and coffee simmered in a pressure cooker can tempt someone to fly to Shanghai just for a fresh try. In the solemn Forbidden City, you can even savor the “Emperor Kangxi’s favorite chocolate”, which is not available anywhere else.

Coffee, once dominated by foreign chain brands, is becoming a playground for domestic brands with traditional cultural elements and a small stream in the emerging Chinese fad wave. We are amazed at how the youth fancy Chinese fad brands, which have swept their social plat form pages and conquered their taste buds. It seems that every young Chinese has been an urban social butterfly with strong national identity, longing for new stuff and knowing how to play.

But why Chinese fad? Why today?

Chinese Fad 1.0Dates Back to a Century Ago

In the early 20th century, once China had lost its independent say on tariffs after the Opium Wars, the domestic market was rife with foreign goods. Amidst the repression, despite the absence of a command center, the national goods movement–raised voluntarily by Chinese entrepreneurs, students and officials–penetrated into the life of every Chinese between 1910 and 1940.

This national goods movement in full swing defined a series of standards in terms of visuals, naming, raw materials, origin and purity of national goods. These far-reaching standards have become convention today. Since the current Chinese fad brands are an extension of the national goods, these century-old standards can guide the design of the followers today, and also enable us to identify the “real Chinese fad brands” with just a glance. Take naming as an example. TASOGARE, the so-called “light of national goods” as CCTV Finance claimed, sounds less “Chinesey” than Luckin (“Rui Xing” in Chinese). As for visual designs, Sexy Tea uses the image of court ladies, a notch above Heytea and LELECHA. However, Luckin and Sexy Tea cannot be seen as first-class national goods, even if we are less strict with the standards, because of their recruitment of foreign technicians and claim of making Chinese tea western.

Of course, China is not alone in the history of national fad. In fact , from the late colonial era to the present day, quite a few countries have pursued a national fad trend a s a way to construct nat ion-state, such as India’s boycott of British goods in the last century and the decision to ban Chinese Apps in recent years.

Consumerism has always played an important role in clarifying national ism.

Today’s Chinese Fad Consumption is Collective and Individual

If the first national goods wave was for the survival of China, the impetus behind the current one is much simpler and clearer: good look, strong interest, intriguing connotation, cheap price, so why not? Some attribute this phenomena to the national wealth and cultural confidence. If we only look at it from this single dimension, it would be difficult to see the whole picture.

When the global pandemic broke out at the end of 2019, the Chinese government took a series of protective measures to control the movement in a bid to reduce unnecessary travel. This resulted in a plummet in international, inter-provincial and inter-city trips , while citizens spent increasingly more time online for remote lessons, shopping, medical advice and entertainment. The “cloud-based XX” became a trend. The sound national cooperation supports China to outperform most countries in epidemic control, whether it was patient clearance or economic recovery. In the global system, cultural confidence has always been associated with economic development.

At the very beginning, the Chinese fad was not positively popular.

The early mass application of Chinese elements came from foreign luxury brands. To please the Chinese market, some brands launched limited products for Chinese New Year, which was opposite to the then mainstream aesthetics in China including Japanese minimalist style and Nordic Normcore. The exaggerated foreign interpretation of Chinese elements was mocked as “netherworld design”, until domestic brands led by Li-Ning brought designs with Chinese aesthetics to the international stage. The cultural output excited Chinese consumers, marking the advent of Chinese fad 2.0. For a variety of reasons, the public aesthetics of Chinese fad has changed drastically in recent years, from only acceptability of Li-Ning’s minimalist design, to the concept of “extreme corny is trendy”, and to the “renaissance” of y2k-style including the Tang and Song style popular on TV shows. Even the previous niche elements have captured a group of fans. This means that the Chinese fad begins to show subdivision and inclusion.

With a close look, we will find the Chinese fad under coffee and tea drinks more interesting. It can unify the taste of young people across the country, but also define individual choice within a province or a city.

When Chinese Fad Steps onto the Coffee and Tea Drinks Track, the Subdivision Based on Local Characteristics Shows Up

China boasts colorful food culture thanks to its wide region and diverse ethnic customs. Based on one’s preferences, we can infer where he’s from and what identity he may hold. As for consumption behavior, Henan people may be more affectionate to their local brand MIXUEBINGCHENG, while Changsha people being proud of their Sexy Tea and Yunnan people of their coffee beans. In Taste and Power , Dr. Guo Huiling suggests that food is a symbolic medium for the transformation between kinship and geoidentity. This also applies to coffee and tea drinks. It started with reputation collapse of international chains like Starbucks and Costa.

Starbucks has long been a leading coffee brand in China. There was a time when white-collars were proud to redeem points for free coffee. However, the brand is obviously not that popular anymore, as customers no longer play by its rules and instead shift to Luckin, A Little Tea and Heytea. Though some may still be excited at the Starbucks’ cat paw cup, the brand struggles to compete with its domestic peers due to low-cost performance, no fresh SKU, and failed multinational decisions to catch local marketing trends. Then Chinese fad came with emerging domestic brands and varied options.

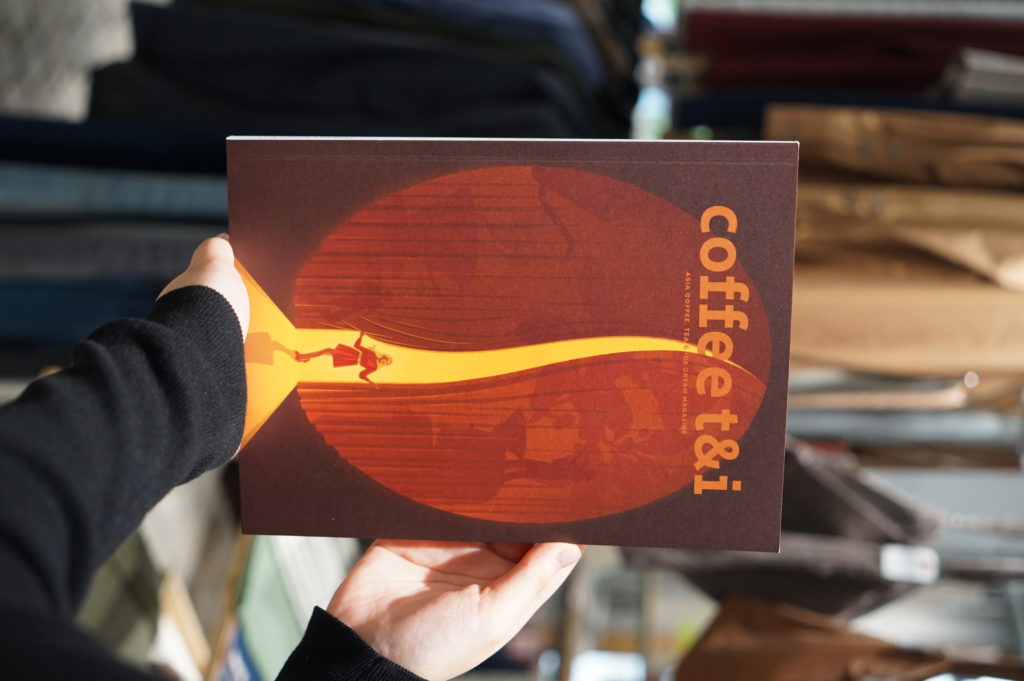

Do Chinese people really need coffee? A few years ago, the answer may have been “no”. The Chinese did not fancy this one of the world’s biggest addictive drinks. For traditional Chinese customers, tea culture is much sexier. Luckin was like a catfish that stirred up the water. Through price war and rapid expansion, the brand allowed every Chinese to clip coupons from capitalism. Then, Saturnbird, YongPu and other brands brought new technologies to the market, enhancing the public coffee consumption habits. As a result, coffee is becoming as normal as soy milk. At the same time, brands for tea drinks mushroomed everywhere. On the 5 weekdays, consumers can order takeaway drinks from ten different coffee and tea brands. These brands have a short decision-making process, launching new products every week to greatly capture the attention of young people.

Regional characteristics show up; the core is about talent return. Just like other cities in the world, big cities in China can siphon talents. To encourage local economic development, build new first-tier city clusters and drive second- and third-tier cities, the Chinese government has been encouraging local governments to introduce relevant talent introduction and training policies. In this context, a large number of young professionals return to their hometown, activating local product design, brand building and marketing. The talent return accelerates the birth of new coffee and tea brands with local cultural characteristics. In this way, the local culture can be passed on through the medium of the two types of drinks.

In Yunnan, for example, the film “Coffee or Tea? ” aired on the 2020 National Day tells a similar story: 3 frustrated young men never lose their passion in growing coffee in Yunnan, despite challenges like parents’ discouragement, friends’ disbelief and unseen gains. Eventually, they not only have their coffee attract the world’s largest brands, but also reap a sense of fulfillment in life. Although the film tends to promote relevant policies, it has helped Yunnan coffee in some way. Since the film, search “Yunnan coffee” on Little Red Book and you can find personal drinking experience and related knowledge as the most-recommended posts; Baidu index, an online tool represents normalized search volum for selected keywords, also shows that the search for Yunnan coffee in the same period has increased 4 times from before. There is no doubt that this film contributed a lot to the growth of Yunnan coffee culture.

Today, the global cultural interchange and trade facilitation have made people’s standard for food more objective. Therefore, we can conclude that the development of the Chinese fad coffee and tea drinks takes advantage of national policies, riding on the rise of regional culture; Commercially, the emergence of regional Chinese fad coffee and tea brands also fuels the regional cultural confidence. However, from a marketing practitioner’s point of view, young people consume cultural brands for more than kinship and regional identity.

Everything is About Figures

When the pandemic accelerates our pace to go online, TikTok, Kuai shou, Little Red Book, Weibo, Dianping and WeChat Moments take over Chinese mass social events, granting ordinary people the opportunity to express themselves and to be seen. How many likes , comments, saves and retweets you can get is directly linked to your dopamine. When consumers move their attention on line , social plat forms also become the new battlefield for brand marketing, unveiling the era of the KOC where everyone shares advertising posts and everyone gets advertised.

A-I-P-L is a set of chain models proposed by Alibaba for user growth and operation. The model represents the 4 stages of the dynamic relationship between target customers and brands within a certain user pool : awareness (get to know the brand), interest (feel interested in the brand), purchase (willing to pay for the products), and loyalty (willing to advertise the brand voluntarily and repurchase). When AIPL is used as a market ing tool , the data of the advertising content released by a KOL can be divided into 4 parts: exposures (A), interactions (I), clicks on e-commerce links and orders (P), and purchases/recognition of favorite brands (L). Usually, when depicted in a chart , these data show up in the shape of a funnel ; The larger the ratio between the 2 numbers at the end and the mouth of the funnel , the more effective the advertising content is. Each coffee and tea brand wants to use this chain effectively to achieve a perfect closed loop of the AIPL, but only those who understand marketing and know how to do it can stand out.

“Picturized rate” guides visual system

“Picturized rate” is a special standard put forward by Huang Hai, Saturnbird’s investor. As he believes, the higher the “picturized rate” of a product , the greater the social media buzz can be, coming with a higher probability of sales conversion. In fact, those Chinese fad brands that have used the “picturized” strategy–intentionally or unintentionally–have a better performance on social media compared to those who haven’t. Take the recent Chinese New Year of the Tiger as an example. Adding elements of tigers, mahjong and spring couplets in products are more likely to be shared by consumers and capture “likes” on social media than normal coffee and milk tea drinks. However, this in no way means that brands should follow trendy themes all the time. The core of a high “picturized rate” still lies in the innovative design of the visual identity system which the brand should always follow while keeping in mind to maintain high standards and clear recognition. For example, Saturnbird can print little tigers on their trademark numbered mini cans, and it is not wise to change the cans to tiger shapes.

Hot topics decide SKU innovations

In 2021, many tea drinks rich in Chinese characteristics frequently gained top searches on social media, such as poached egg ramen milk tea, beef ramen milk tea, Duck poo oolong milk tea, spicy pepper and tender tofu milk tea, among others. The complicated tastes made us frown but we could not help clicking them. Most of these innovative products failed to make consumers remember their brands, and it was also difficult to form a competitive barrier. However, when travel is restricted today, these courageous products can win heated discussion and massive orders for the brand. They are even able to go beyond geographic and cultural limits, helping the brand break the consumer group barriers. In the long run, it is possible for them to bring greater opportunities for the brand.

Interactive activities determine user retention

It is worth mentioning that Starbucks bakery buffet, Nescafe’s offline experience store and Saturnbird’s can recycling program all try to bring consumers a more intimate brand experience in the era of online social community. Despite the varied results, the short-time reputation collapse or popularity won’t stay long in the shared memory of the hundreds of millions of young people in this land. On the contrary, activities which encourage the youth to go out can provide them with chances to share their life on WeChat Moments, thus an excellent way to build an intimate brand image. In the fast-paced life, it is especially cozy to spend an afternoon under bright sunshine while sipping a cup of fresh coffee. It is more relaxing than kicking off a busy day by pouring powder or liquid from a small jar.

Targeted marketing boosts repurchase

Entering the store, ordering during the livestream… Such behaviors will be recorded to form customer groups. The crowd will be classified with hundreds of tags such as passersby, new customers, loyal users and silent users; Tailored content will be delivered to different groups in order to stimulate orders. Marketing methods like tagging the crowd, speculating on their needs and providing customized content/services are nothing new, while some users are happy with the customized services. Systematic user management is one of the ways brands can grow wildly. For greenhorns in this playground, there are clearly more challenges. No matter what, in the KOC marketing era, good figure performance means the worth of love. Good figures bring a probability of being loved.

For consumers, products featuring trendy topics and the possibility to draw figure-based recognition are worth multiple times of trying and sharing. For brand owners, it is worth serious review and a second try if one strategy can bring better figure performance on the AIPL chain.Therefore, the young people may not like or only fancy the Chinese fad. They are just playboys who love whatever they feel is fresh.

So, What Kind of Brands Would Young People Prefer?

The popular words “involution” and “take it easy” have lasted from 2021 to 2022. This means that, despite a seemingly upward environment, young people’s confidence in the future is still going downside in the context of the pandemic and the high living expense. We can naturally find a million reasons for this trend, such as the rapid development of the era, the prevalence of consumerism, and the peer pressure enhanced by the Internet which breaks the information barriers, among others. But we can just simply catch one key. Young people may spend 20 yuan on a cup of milk tea printed with “getting super rich”, or rush to McDonald’s to buy 2 coriander ice creams. In fact, these behaviors are their fight against the banal daily life. Chinese fad coffee or milk tea is like a dose, a lipstick, a social attempt with a high mistake tolerance rate, and a self-satisfied expression for kinship and patriotism. They use consumption to hold their life vision for a short time, and harvest some recognition in cyberspace. From this perspective, the youth would prefer those brands that enable them to find an anchor for their lives in this changing era and offer them real experiences.

Will young people still like the Chinese fad coffee and tea drinks in the next few years? I’m not sure. Perhaps we need to wait until the day when the COVID-19 pandemic no longer restricts our traveling, and when consumers can experience products at ease and today’s flourishing brands need to be tested again by the market.

NO COMMENT